Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: Hello and welcome to another installment of Unraveling Religion. I'm your host, Joel Lesses, and I'm here with a very special guest, Rev. Brian. How are you doing today?

[00:00:12] Speaker B: Wonderful. It's great to talk to you.

[00:00:15] Speaker A: It's great to talk to you too. Yeah. Just before we started the recording, I know we were talking about sort of what was the word divine providence, the word in Hebrew, what was that which. Which translates as.

[00:00:32] Speaker B: It's the idea that things are unfolding according to an underlying intelligence that we can't see. And so in a way that's. That's causal, beyond what we can't see as well. So the people we meet, the things that happen to happen, so that we might attribute just to randomness, are unfolding in order to bring about certain purposes that are beyond the. Beyond the surface.

[00:01:04] Speaker A: So that resonates so deeply with me. Both initially, that used to resonate with me intuitively. I used to feel that, like, my God, there's divine providence, there's this sort of like, plan that's unfolding.

And then I think as I began to assess sort of these coincidences or synchronicities that just were seemingly beyond just probability, it really began to take hold in my mind. And so I really fully feel as a. As a full, embodied human being that this notion of Divine Providence is the reality in which we are living.

[00:01:42] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah. And I really. I see this idea on. In at least two different levels. On one level, even if we don't experience coincidence, you know, things magically coming together in a special way, which usually people experience that once in a while. It's not necessarily something you experience all the time. Yeah, but what does that mean, that we experience it once in a while? It means that the various things that were not seemingly connected in our lives, we were able to see how they were bringing about some wonderful result, hopefully. Wonderful.

But we can see. We can see how things are conspiring together to create something. But the reason why that's amazing to us is because all of the ways in which everything conspires in an obvious way to bring about life itself. The fact that we exist at all, the fact that we can get up in the morning or do anything, those things we take for granted because they're so constant. So hashgacha pratit is actually the most common thing we experience, but we're kind of oblivious to it because we're used to it. We expect that we'll wake up in the morning and take a breath and be able to get out of bed. And so on. And yet that's an infinitely mind boggling confluence of forces that have to come together to make all of that happen. So only when the. Those unusual coming, comings together happen are we able to really notice it. And then we say, oh wow, there is an order to things, right?

[00:03:29] Speaker A: Just to see, just to hear, right? Just experience.

[00:03:32] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Just to. Just to be. Just to. Just to be. Just for have, for having this body work, to have relationships with other beings that we can look into their eyes and we can understand each other with language. And it's all providence. But so that's one level of it is that when we experience things like that, or also things, we could also apply this to things that we call miracles. Really everything is miraculous, but it's only certain things that wake us up to that. And so the hope is that those experiences can not only give us an idea in our mind of the order of things, but can help us to be sensitive to that order that's happening all the time around us and within us and so on. So that's one level of it.

Another level of it, though, even a little deeper I think, which takes a little more effort, is that when we experience chaos, which is also very real, things not working, things not coming together and so on, that if we hold in our minds the idea that things are nevertheless perfect.

Perfect for what? Perfect for the. Our own evolution, for the growth of our own consciousness, then we can choose to engage whatever's going on, however chaotic it might be, in order to bring about a positive result in a way that we may not have been able to do had we not been able to step back and appreciate the potential within what's going on. So that's. Those are the two positive ways that I see that idea kind of playing out in terms of how we can use it to become more conscious.

[00:05:22] Speaker A: A part of that is waking up. Right. Awakening or waking up.

[00:05:26] Speaker B: Right.

[00:05:27] Speaker A: But maybe people are on the cusp or the verge. Maybe then they have like a intuitive sense. But what does that mean? What does it mean to wake up? What do we wake up to?

[00:05:40] Speaker B: Well, on the deepest level, we wake up. Well, first I would say, I would phrase it not so much as waking up to, but I would phrase it as waking up out of.

Because when we wake up in the morning, for example, if you're having a dream, we wake up out of the dream and we wake up to whatever is going on in the space that we're in when we, when we awaken out of sleep. But the difference is that when we're in the dream, it seems real. And we think that these things are going on that are. That the drama. Whatever drama is unfolding in our dream is really happening. And then when we wake up, we realize, oh, it was just a dream. Well, what does that mean? It was just a dream. Means there's a level of reality to being in waking life. That's different from the reality of the mere experience of being in a dream. Which doesn't seem to have the same types of consequences. The other beings aren't real. They're probably generated by our neurons and so on. And so there's something also that we tend to.

There's a dream that we tend to be in when we're in waking life. And that dream is the dream of who we are.

Meaning we feel our identities to be bound up with our bodies, our thoughts, our feelings. And of course, our thoughts and feelings include our whole history, our whole sense of direction of where we're going, of the roles that we play in the world. And all of those are real. But the part that's dreamlike about it is that we think that that's all we are. And so in the experience of what many people call spiritual awakening. There is a shift in the experiential sense of who you are. So as to recognize that you are not all those things. You are not merely your personality. You're not merely your body. You're not merely your feelings and thoughts and so on. So what are you then?

Well, that's kind of beyond words.

Even. Even the. The sleep part, the dreaming part is also kind of beyond words. Because we don't usually go around thinking, I am my body, I am my thoughts. We don't think those things. We just take it for granted. It just feels like what we are. But there's. But there can be an experience of feeling like you're something completely different. And that other thing we could describe as spaciousness, as pure awareness, pure consciousness.

And all of these things are present all the time for us. But we don't feel that that's what we are. We feel that consciousness is just something we have. Like, I'm conscious, I'm aware of, you know, I'm aware of what's going on around me. I'm aware of the sounds. I'm aware of my thoughts. I'm aware. But the awareness is like a property that we have or a faculty that we have, right? But when we shift into that awakened state.

Which happens in different ways for different people, but the one common thing at least in the various reports that I've seen and in my own experience of it is that it's like, whoa.

Everything that I felt was so important all my life, I felt was important because I was looking at it from the point of view of being this ego self, this separate self, or this bundle of thoughts and feelings inside a body, looking out. And now that I feel like I'm basically nothing, I'm just. I'm just awake. Spaciousness. I mean, that's a way of putting it. What we felt was important and what we felt was crucial. And that both the positive and the negative just no longer has that same pull and everything seems completely different.

[00:09:46] Speaker A: That makes a great deal of sense. And what I hear you saying is that awakening itself is a process of letting go or dropping, not adding on to.

[00:09:56] Speaker B: Right, yeah, that's absolutely true. However, there is a little. I just want to qualify it a little bit because it can happen. And I've. I've seen reports of this happening. I don't know that I've known someone personally who this has happened to, but I've seen plenty of writings about this where people have a spiritual awakening experience. And because they don't have the intellectual map in their minds for what's going on, it doesn't.

They don't work with it and deepen with it. They just kind of go back to regular life and it fades away eventually and it's just treated as a weird experience.

So in a way, it's true that the actual awakening process is a letting go and a.

Because there's a deep emotional attachment to the way we see things and feel things in that awakening experience that does. Part of that involves a kind of letting go of the familiar and what we're. Our conditioning and many other things. But in order for that to really have a lasting effect and to kind of have a forward movement in our lives of deepening and embodying this awakened consciousness.

I think it's really important to understand about it also in an intellectual way. And that's why it's fine to learn about it and to have these ideas while you're practicing. Even before you have any kind of awakening experience. When you begin meditating, you have a glimpse of that awakening right away, you know, even if it's not a very radical experience. And having that intellectual map or construct of what it is and also just clarifying it more and more and having it clarified by people who are good teachers allows a person to deepen with it and develop with it. Even without such a radical, dramatic kind of awakening, experience, the mind itself.

[00:11:52] Speaker A: In Zen, you know, there's a state of what they call Buddhahood, which. Which is known as motion, which is like empty mind. I hear this is a sort of departure from the Jewish notions of spirituality, Kabbalah and awakening, that the intellect is a faculty that is important and utilized in the spiritual development and awakening. Is that true?

[00:12:15] Speaker B: Yeah, yeah, very much so. I mean, Judaism is such a. Has such a rich intellectual dimension in general, so the mystical aspect is also going to have that. But I would also argue that in other traditions which emphasize the emptiness and going beyond the mind, that itself, even the fact that we're just saying that and communicating that is an intellectual map that we're giving people, we're saying, let go of the mind. Let go of the constructs of the mind. Well, that's already a thought in my mind that I'm going to let go of it. So even though it's a very simple thought, it's not some elaborate system, it's still a far cry from just having the awakening happen without any preparation, without any tradition, without any instruction. It's really there in all the traditions.

And if they say no mind, the very saying of it is mind.

[00:13:16] Speaker A: Agreed, Agreed.

Some questions for you, like, maybe, like, if you could talk a little bit about just the fundamentals of Judaism and start maybe with like, what is Kabbalah? What is Kabbalah? What does it mean? Where does it come from? Who's it for, and what does it offer?

[00:13:34] Speaker B: There's a lot of complexity to it, but I want to cut through all that complexity to get to core. And from that core, we could look at the different aspects of the complexity and have some sense of what we're talking about.

In the most simple sense, in the most simple core, Kabbalah is just Jewish spirituality. Judaism, as well as all other spiritual traditions, began with some kind of spiritual experience, either of an individual or groups of individuals.

In the case of Judaism, we have the stories of the patriarchs and matriarchs talking to Hashem, getting messages and so on. And regardless of whether those stories are literally true or not, they point to the origins of the tradition as being as stemming from some initial encounter. And even in the Torah itself, those encounters are very, very simple at first. Later on, it becomes this whole system of laws that becomes the foundation of the Jewish tradition, which is extremely complicated. But the encounters were very, very simple.

And when the Torah has God speaking as a character in the narrative, the first kinds of things God is talking about is just whether a person is Like a decent person or not. Not all these laws about what you eat and special holy days and sacrifices and all this St. But like Abraham. I like Abraham because he's a good guy. You know, it doesn't say it in those words, but that's the essence of it. Noah. We're going to put Noah in the ark because, you know, he's. He's good in my eyes, whereas everyone else is all corrupt. He's the one guy who didn't get corrupt. He's already. He's good in just as a person. He's a good mensch. He's a good person. As traditions develop in general, and certainly Judaism particularly, it accumulates tradition. One of the hallmarks of a tradition is that it accumulates more and more material over time because as people contribute to it, it grows. And it has to keep everything from the past. The things it doesn't keep, we don't know about. But everything that gets carried on in the tradition has to be tied in some way to the new stuff that's coming. And so you get this superstructure that grows and grows and grows.

The tendency is for a tradition more and more to become about that superstructure of intellectual scholarship and complex practices and rules, and less about that simple encounter that is referred to in the early stories of Genesis.

Then again, in the life of all the traditions, but especially in Judaism, there come various points in history where there's this impulse to return to the essence.

Martin Buber called this renewal.

That was the beginning of the term Jewish renewal, by the way, which was created in the 60s by Reb Zalman, Schachter Shalomi and others. He's considered the grandfather of it. But many, many people contributed to this beginning of the Jewish renewal movement. And it was based on this term that Buber originally said, which is that in Jewish history there are. There are moments of renewal.

And early Kabbalah was such a renewal movement. Hasidism was even more so, a kind of renewal, because even though Kabbalah was. Was an attempt to get at the spiritual essence beneath the words, beneath the practices, beneath the various traditions, it was still a very elitist phenomenon because those who were involved with it were educated, well off learned men. When Hasidism started, it came into the world in order to address the crisis really of peasant unlearned Jews being completely disconnected from the tradition because there was this hurdle that they couldn't get over. They didn't have the time. The me means to study. And so the BAAL Shem Tov, who's thought to be the founder of Hasidism, although it really started before him, but he's the first main character that we know about in his writing or his teachings that were written down by his disciples, came to say, hey, you don't need all that scholarship. You should try to get it if you can. It's not that it's not important, but it's not the essence.

So the essence is an inner sincerity, an open heart, and a desire, a sincere desire to connect with the life of all worlds.

And all of his teachings are really aimed at helping you, first of all, to have the confidence to do that. That's like 99% of the battle won. Right There is just to know that Hashem, or the divine or reality, however you want to say it, it's available to us right now. And then the rest of it is. Is the how to.

[00:18:55] Speaker A: That's so beautifully stated. And I know you have.

[00:18:58] Speaker B: You.

[00:18:58] Speaker A: You have Torah of Awakening, which is your. The ages of your. Your teachings. Right. You have the three portals of presence, spiritual awakening. And you were talking about an open heart, and I know that that's the first portal, right?

[00:19:13] Speaker B: Yes. Yeah.

[00:19:14] Speaker A: You say a little bit about that, about maybe talk a little bit about Tour of Awakening and the three portals of presence.

[00:19:22] Speaker B: Sure. So when we begin a meditation practice, we usually do so because we have some aim in mind. We're trying to get at something. Maybe we want more inner peace, we want less stress, maybe we want healing. Maybe we have more of a spiritual frame for it and we want to come closer to God, closer to Hashem, or we want to realize the truth. Whatever it is, there's some reason we do meditation. We don't just do it for no reason at all.

The problem is that when you have a reason, you have an agenda. You're trying to get somewhere which is not where you are.

And that in and of itself is the opposite of meditation.

Right. I mean, this is true, I'm sure, in your world as well. In the Zen world, you don't go to the Zen center and practice just for nothing. You have a reason why you're coming to do it. And yet the essence of meditation, which I think is expressed most clearly actually in Zen. I've seen this expressed most emphatically in Zen, is that you're giving up your agenda. You're being with this moment as it is, you are not having some aim other than this. This is your aim. Right.

[00:20:44] Speaker A: Actually, they say it beautifully. Matheson, Peter Matheson, who died in 2012, he wrote the Snow Leopard, among many other works. He was a Zen priest and he said beautifully in the snow leopard and nine headed dragon river at this moment is a scripture of Zen. And that's. That's kind of nice.

[00:21:02] Speaker B: Yeah, that's wonderful.

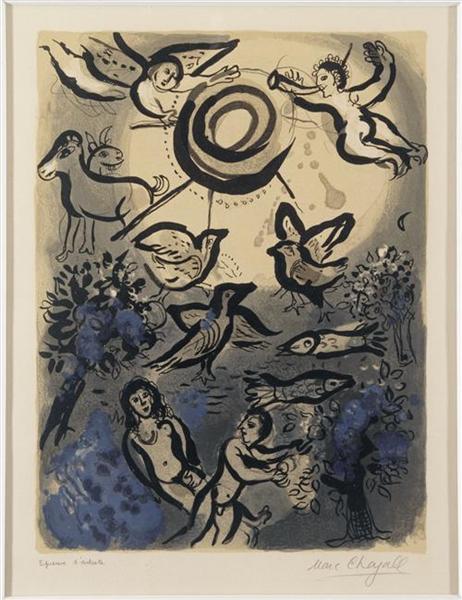

The reason that I begin with the Portal of the Heart when I instruct meditation is that I am encouraging people to get out of the agenda mindset and to instead invoke our capacity for presence with. What I'll do is I'll usually give a thought experiment when I'm first teaching it, such as a situation where a little kid comes up to you and shows you the picture, picture they drew. I don't know if you saw that in the book that I. It's in. I think it's in the beginning of that book, that image of like little child comes and shows you a picture. What is your experience in that moment when that happens?

Probably you smile and you appreciate and that's it. It's very, very simple. You're. You're giving your attention to the child and to the picture that they drew. Not because you're trying to achieve something or get to some certain state or anything, or become less stress, anything like that. It's just a spontaneous warmth from your heart and that the attention that you're giving is infused with that heart warmth. And so that's what I'm trying to encourage people to tap into. That's obviously it's a capacity that we have. It's evoked spontaneously in a situation like that with the child in the picture. But we can also evoke it from within ourselves at will if we have that intention. So that's all. It's a matter of attitude, you know, taking the attitude of giving your attention from your heart to this moment. And that's what I believe in Buddhism is probably called like, right, intention, like having that. I don't know if it's stated in that way exactly, but the intention of being sincere and true and heartfelt, just being with this and not having something, anything else as your agenda other than this. And so that's why I begin with the Portal of the heart.

[00:23:06] Speaker A: One of my favorite illustrations of that was Rabbi Yaakov Yosef of Polnoy.

[00:23:11] Speaker B: Yeah.

[00:23:13] Speaker A: Are you comfortable sharing that story or.

[00:23:16] Speaker B: Oh, sure, yeah. I love that story. So the story goes, was Rabbi Yaakov Yosef of Polnoi was later became a disciple of the BAAL Shem Tov, who's the founder of Hasidism. And so this story takes place before he met the BAAL Shem Tov. So it kind of sets the stage for. And this is why the story is told in Hasidic circles. It's like, well, why did the BAAL Shem Tov pick Yaakov Yosef? Well, this is part of the reason why he was picked.

So the story goes that he was an incredible scholar, and he was kind of a genius of Torah. And he was also a recluse, which is a characteristic that's common for mystical leaning types and very intellectual types as well, usually not so gregarious, tend to want to be alone and study and so on and not go to social functions. That's with the way he was.

But he was invited to attend a Brit mila bris, which is the circumcision ritual, circumcision of a baby boy. And it's considered a mitzvah. It's an obligation if you're invited to such an event that you have to attend. So he was getting ready to go out and reluctantly to go and attend this bris. And he opens the door to go outside, and it's pouring, raining outside, so he didn't want to go anyway, now it's raining. So he puts on his big coat and boots and he trudges out in the mud and makes his way to the house where the bris is happening. And when he gets there, he's the ninth guy. And if you know in Judaism to do something like that, you need to have at least a group of 10, a minion of 10, it's called. So they need one more person to make the minion. So he goes outside and tries to see if there's anyone else coming by, really. He really wants someone to hurry up and come in so they can finish this thing.

And he sees this old beggar coming down the road, and he says, please come help us make a minion. The beggar says, so be it.

So he comes in and they make the. They do the ritual. And afterward the host comes and offers the beggar a little chayyim, a little drink. And the beggar says, so be it. And a little bit later, someone comes and offers the beggar some food. And he says, so be it. So Rabbi Yaakov Yosef becomes curious, and he goes up to the beggar. He says, so what is your story anyway?

No matter what anyone says to you, all you say is, so be it. And the beggar says, which is the beginning of the ashrei, which is mostly Psalm 145 with some other verses in the beginning. And. But it's very famous in Jewish liturgy. People who daven know the ashrei. And those words mean happy are those who dwell in your house forever. They will praise you. And so Yaakov Yosef says, okay, so what? So you said the first line of the ashrei, so what? And then he says the next line, which is ashrei haam sheikah lo, which means happy are the people for whom this is so. But he, when he said it in the Yiddish, when he was speaking in the Yiddish, he translated it a little bit differently. Normally it means happy are the people for whom this is so. But he translated it, happy are people who accept that which is so.

And Yaakov Yosef heard the mistranslation, he heard the twist in the translation. He said he was kind of taken aback for a moment, and then he looked and the beggar had vanished.

And he what happened? Who was that guy? He starts saying in his mind, as happy as a person who accepts that which is so. And it's like a gong went off in his soul, and he was kind of stunned and he just walked outside. He starts walking home and he's repeating it over and over in his mind, asrei haam sheikochalo. And he begins to awaken in a sense. He begins to realize that his relationship with his reality, with the present moment, his experience in the moment has. Has been one of resistance. Not just this day where he was in a bad mood for having to come to the brisk, but in life in general. He never realized that his relationship to life was contracted, was closed, and he started to open, he started to blossom, open like a flower. And the story goes that that old beggar was Eliyahu Hanavi Elijah, the prophet, who had come to teach him this lesson. So it's an awakening teaching. It's a very, very simple awakening teaching, like, accept life as it's coming.

But that teaching is all through Judaism, and yet it's hardly ever talked about. It's never put forward as the central teaching of Judaism.

And I, in my life, I've just saw that as a strange problem. And I see other traditions such as Zen, which do put that forward front and center.

And I think that that's important. And especially nowadays where we.

I shouldn't. It's not just nowadays. It's really the last few hundred years, maybe since the. Since the European Enlightenment, where the religious assumptions and dogmas that held sway really dominance over the minds of humans all over the planet has begun to crumble. There are a lot of people who still believe in all that, but it's not the dominant way that people think anymore. And so why should I care about religion? Why should I care about these spiritual traditions? Well, if you don't know that there's an essence that's actually helpful to you, and if it's just about these strange belief systems that you kind of have to be crazy to believe in a literal way completely, then you're going to throw away the baby with the bathwater. You're not going to realize that there is an essence. And so that's what Kabbalah tried to do, was bring out the essence in its own way. But that was in medieval times. That was in a very different time. Hasidism did it, but that was in a time when the problem was illiterate peasants.

They still had those traditional assumptions. But today we have to get really serious. I think we have to really recognize that spirituality is essential for being able to survive on the planet. Because if we don't have that spirit of openness, if we don't discover that portal of the heart, first of all, there's two other portals, but at least the portal of. At least the portal of the heart. And we're not going to be able to communicate, we're not going to be able to work together as a species to deal with the various challenges that are coming forward.